Process transparency

Contents

Process transparency¶

Now let us consider process transparency. We aim to answer three questions:

What information falls under the category of process transparency.

Why stakeholders can be interested in such information.

How such information can be managed and communicated.

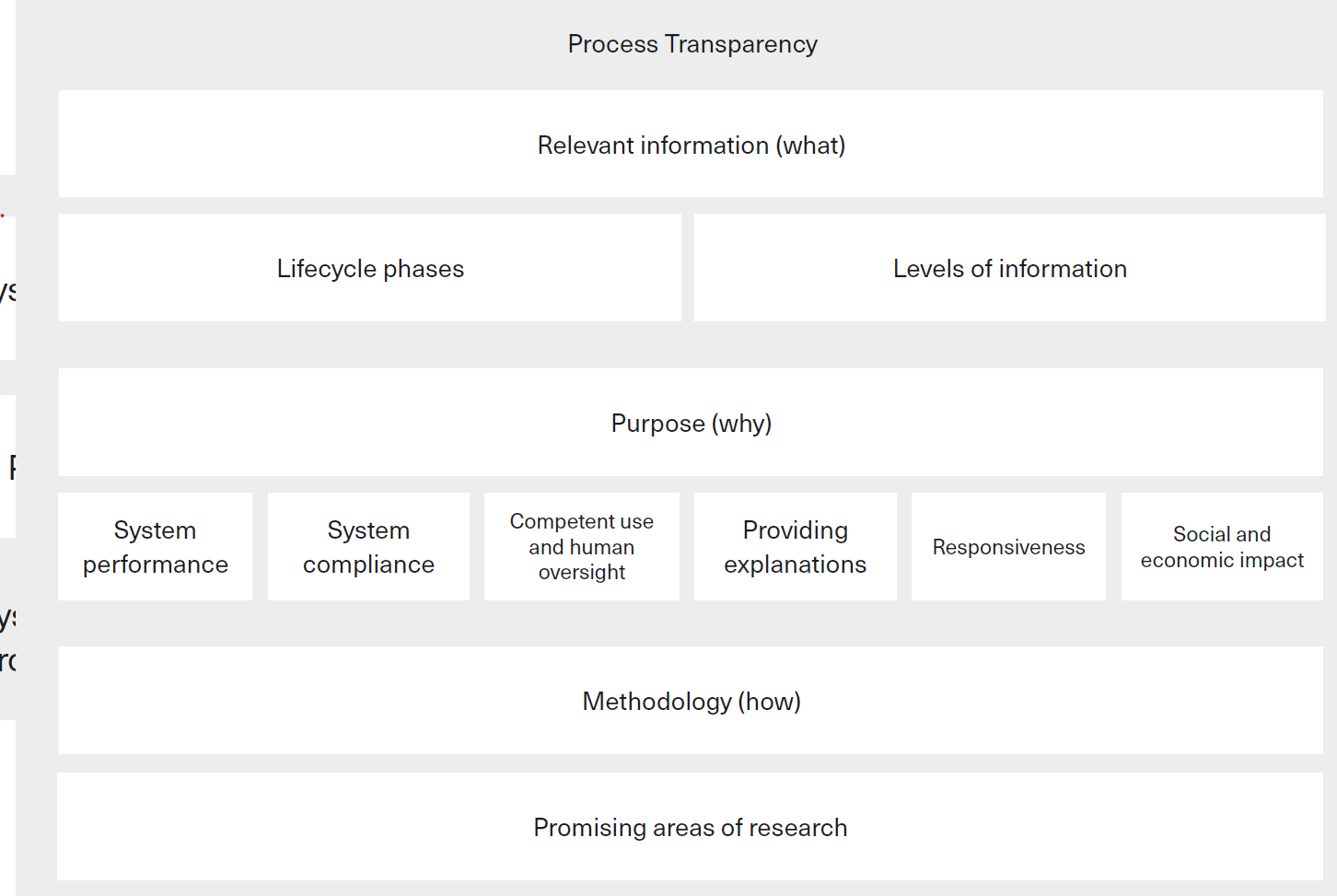

Fig. 3 summarises process transparency in the three key questions above.

Fig. 3 The what, why, and how of process transparency [Ostmann and Dorobantu, 2021] (maybe redraw later).¶

What relevant information?¶

Process transparency concerns access to any information about an ML system’s design, development, and deployment apart from the system’s logic. As with system logic information, such process information is important for addressing and providing assurance about concerns raised by AI systems. Correspondingly, there is a growing amount of work on how process information can be recorded, managed, and made accessible in practice.

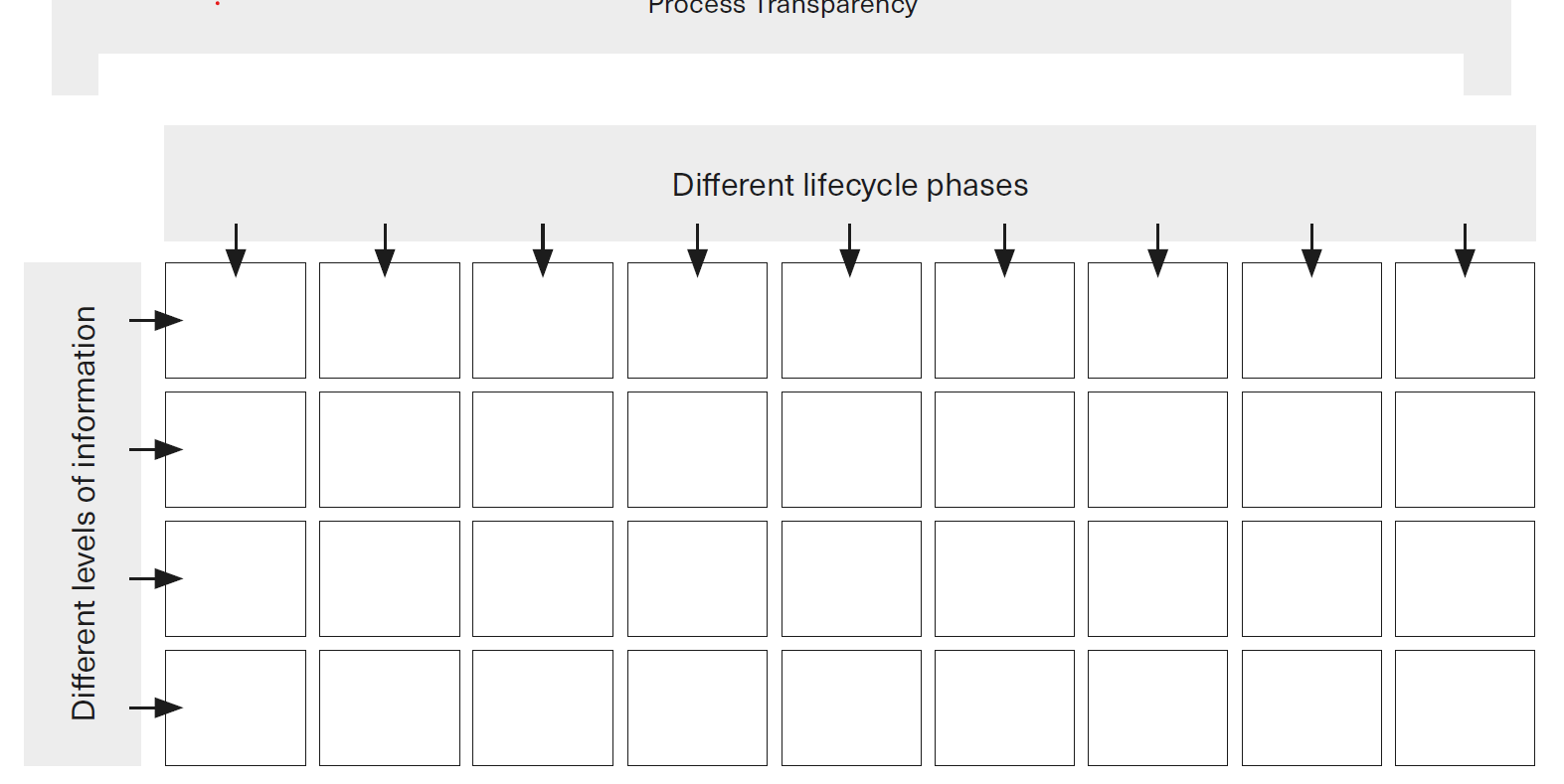

We can categorise process information regarding ML systems along two dimensions:

Different lifecycle phases: Process information can relate to (i) the design and development or (ii) the deployment of an ML system. In both areas, more specific lifecycle phases can be distinguished, each of them associated with unique aspects of information.

Different levels of information: In considering a given lifecycle phase, different levels of process information can be distinguished, corresponding to the kinds of questions that the information serves to answer.

These two dimensions lead to a typology for process information whose general structure can be represented in the form of a matrix, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4 Process transparency matrix [Ostmann and Dorobantu, 2021] (maybe redraw later).¶

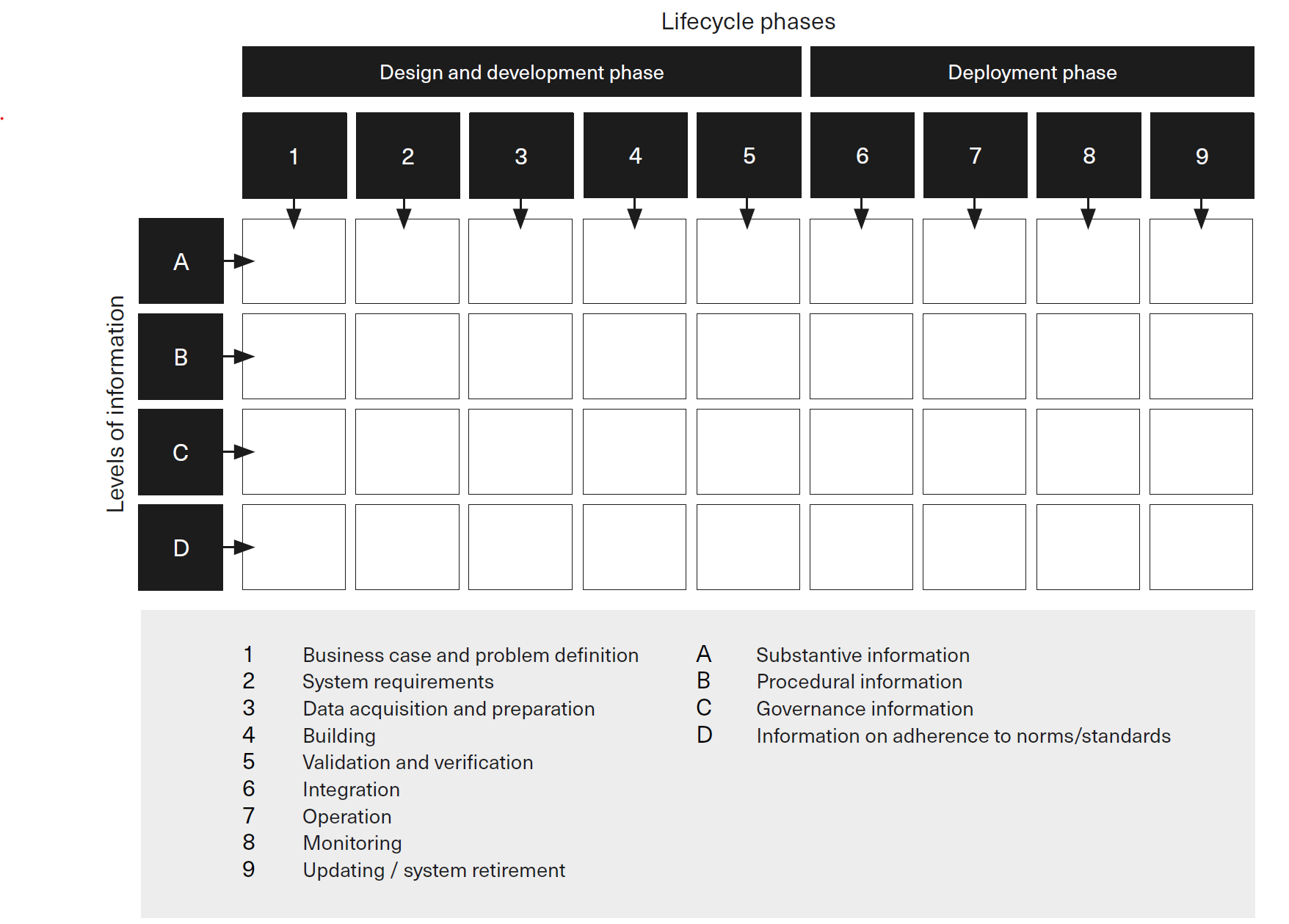

Let us study the different levels of information below. For each lifecycle phase of an ML system, there are various aspects of information that can be of interest to internal or external stakeholders. These aspects of information can answer questions at different levels of abstraction. The following four levels of information can be distinguished, moving from more concrete to more abstract questions:

Substantive information relates to questions about substantive aspects of activities within a given lifecycle phase for an ML system. Examples of such information include: the content of problem definition or system requirement statements; the content of or summary statistics for datasets used during the ML system’s development and operation; source code or other formal representations of the ML system; and the results of tests conducted to assess system performance or compliance.

Procedural information answers questions about the procedures that were followed in performing the activities within a given lifecycle phase. Examples include descriptions of: the process that led to the agreed problem definition or system requirements (eg the actors and the steps involved); the procedures employed to collect and assemble the data used during the ML system’s development or operation; the nature of data quality checks or processing steps carried out; the process followed to select the type of ML method used for developing models; or the procedures used to conduct system tests.

Governance information answers questions about governance arrangements for activities conducted within a lifecycle phase. This information may take the form of statements of accountability and liability, or descriptions of the structure of relevant oversight mechanisms (including, where relevant, the role of risk and compliance teams, ethics review boards, audit teams, senior managers, or board members).

Information on adherence to norms and standards refers to compliance with norms or standards in the design, development, and deployment of an ML system. Such norms or standards may touch on substantive, procedural, or governance questions.

The distinction between these four levels of information remains unaffected by the complexities of sourcing data for ML systems or technology supply chains. Where firms rely on third-party providers, all four levels of information can be applied to activities carried out within and outside the firm. Additionally, relevant governance information in such cases can include information about accountability structures and mechanisms that govern the relationship between third-party providers and the firm employing the ML system in question. These four levels of information, combined with the typology of lifecycle phases, lead to a more concrete version of the matrix we introduced at the beginning of this section to map out different types of process information.

Fig. 5 incorporates specific categories into Fig. 4.

Fig. 5 Detailed process transparency matrix [Ostmann and Dorobantu, 2021] (maybe redraw later).¶

Why such info?¶

Process information, like system logic information, can help to address concerns related to AI systems (ensuring the trustworthiness and responsible use of these systems) as well as to provide assurance that concerns have been addressed adequately (demonstrating trustworthiness and responsible use). In the following paragraphs, we illustrate the importance of process transparency in addressing each of the six areas of concern as in Fig. 2.

System performance: Information about the content of system requirement specifications, about the quality and origin of data used during an ML system’s development or operation, or about validation procedures is crucial for understanding the effectiveness, reliability, and robustness of ML systems. This information can be of interest to those involved in or making decisions about the development and use of an ML system, as well as those seeking assurance about the system’sm performance (eg members of audit teams, board members, regulators or customers).

System compliance: Process information is crucial to assessing ML systems’ adherence to compliance requirements. For example, information about the quality of data used and system tests conducted is essential for a holistic understanding of potential risks of unlawful discrimination. Similarly, where ML systems use personal data, information about the provenance, content, and quality of this data is important for data protection assessments. Process information can be of interest to those ensuring system compliance or can demonstrate system compliance to stakeholders.

Competent use and human oversight: Information about an ML system’s intended purpose, system requirements specifications, or system performance measurements can be essential to ensuring competent use and preventing the inappropriate repurposing of ML systems. This information can also be crucial to determine what forms of human oversight are needed and to enable overseers to exercise their role effectively.

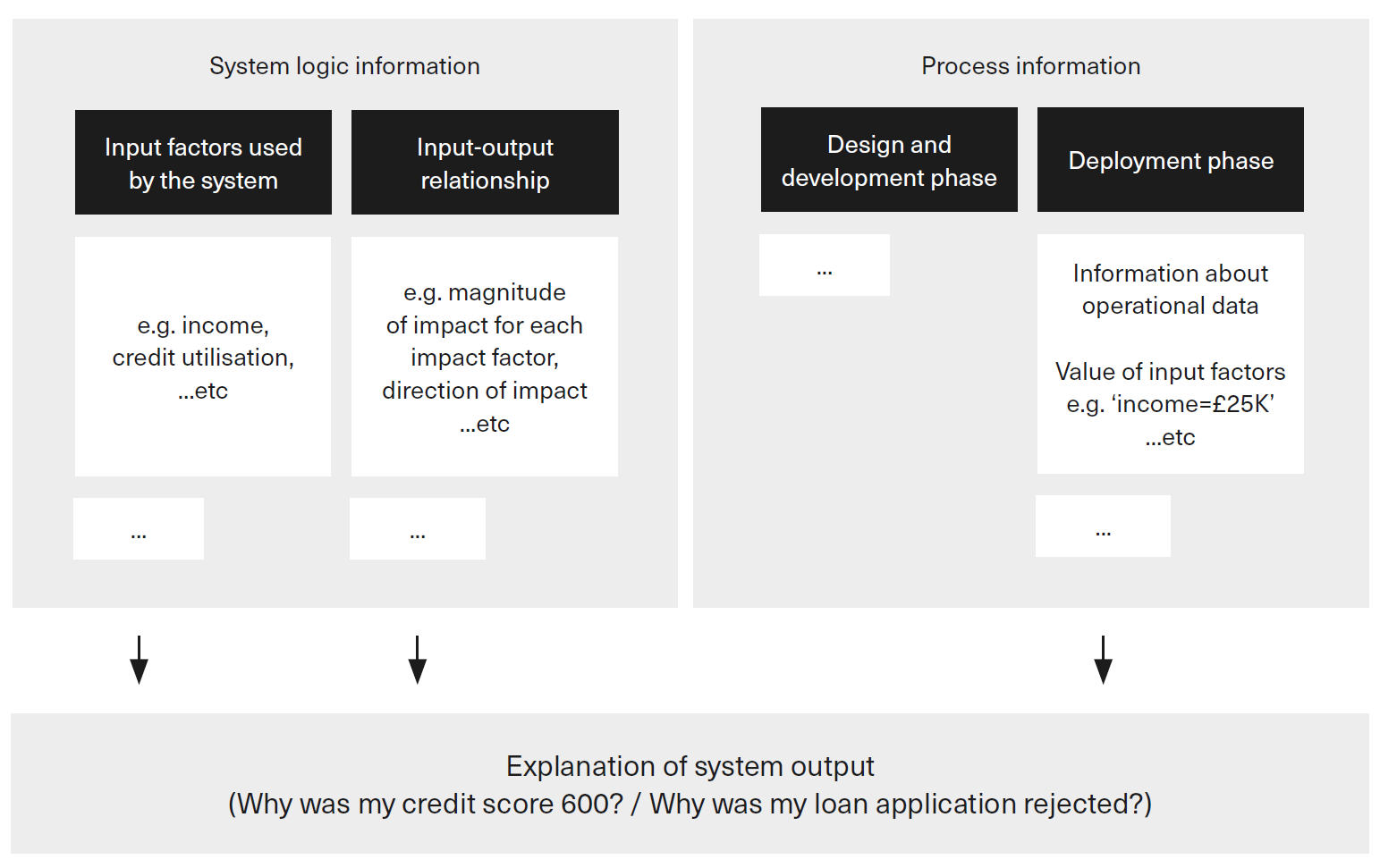

Providing explanations: Explanations of an ML system’s outputs can involve system logic information as well as process information. Indeed, a complete understanding of a particular decision requires both. Fig. 6 illustrates this using the example of a loan eligibility decision. In terms of process information, decision recipients seeking to understand an outcome may want to know the content of the input data about them that an ML system used. This knowledge is a precondition, for example, for being able to identify erroneous decisions.

Fig. 6 The combined relevance of process and system logic information in explaining system outputs [Ostmann and Dorobantu, 2021] (maybe redraw later).¶

Responsiveness: Telling users about ways in which they can ask for information, help, or redress is important to reassure them of the existence of pathways for expressing such requests. In addition, internal stakeholders may need access to different forms of process information, such as the data used during an ML system’s operation, to be able to respond to customer requests. Finally, stakeholders seeking assurance about the responsible use of ML systems may be interested in information about how issues of responsiveness are managed.

Social and economic impact: Various types of process information may be needed to manage and provide assurance regarding the social and economic impacts of an ML system. For example, information about system test results can be important for understanding an ML system’s potential financial exclusion implications. Similarly, information about how firms communicate personal data use to customers can be of interest to stakeholders seeking assurance in relation to concerns regarding consumer empowerment.

How to manage such info?¶

The appropriate level of detail and technical sophistication in providing process information will depend on the purpose that the information is meant to serve. For example, actors involved directly in the validation of an ML system are likely to need a system requirements statement. Customers or other stakeholders interested in ensuring that the right procedures have been followed in validating an ML system will likely need less detailed information, expressed in easy-to-understand language.

Existing best practices within firms – even if they are not specifically designed for ML systems – can guide the process of identifying suitable ways of recording and presenting process information. We consider three areas of research and development related to managing and communicating process information below.

Recording and presenting process information for ML systems: Recent years have seen a rapidly growing literature on topics such as documentation, assurance, traceability, and audit trails for ML systems. Contributions to this literature often give examples of how different aspects of process information can be recorded and made accessible to different stakeholders. In many cases, these examples involve proposals for different ‘documentation artefacts’ and templates that can be used to structure process information in practice.

Some contributions to this debate are focused on subsets of process information or the information needs of particular stakeholders. Increasingly, however, contributions adopt a holistic perspective on documentation needs, covering all phases of an ML system’s lifecycle as well as the information needs of all relevant stakeholders. An approach that is growing in popularity – especially in the context of high-stakes applications of ML/AI – is the use of ‘argument-based assurance cases’, often following a specified template, in support of claims about an ML system’s properties.

Recent years have also seen an increase in the number of open-source tools for testing ML systems and examining their properties. These tools can be useful for generating some of the process information that is of interest to stakeholders.

Emerging norms and standards: A second evolving area with relevance to managing and communicating process information consists of work on standards for ML systems and on professional standards. Several national and international bodies are currently working to develop standards for ML systems. These standards serve as a useful point of reference though their applicability to real-world use cases will depend on context.

In addition, recent years have seen growing support of initiatives to professionalise the field of data science. Efforts in this space are aimed at establishing commonly agreed curricula for data science courses and possible forms of professional accreditation for data scientists. For example, a group of professional bodies led by the Royal Statistical Society (RSS) is currently working to develop commonly agreed professional standards for data science.Concurrently, some professional bodies in the financial services space are turning their attention to codes of conduct for the use of data and emerging technologies.

Mechanisms for verifying process information: A third area of emerging work concerns the verifiability of process information for ML systems. This includes forms of independent certification for relevant norms and standards. Currently, declarations of adherence to norms and standards take the form of self-declared adherence (‘self-certification’). However, in some contexts, stakeholders may place greater trust in such declarations if they are supported by independently administered certification or labelling schemes.

There is also an emerging literature on the role of auditors in examining system design, development, and deployment processes (including evaluation). In contrast to certification, auditors may verify process information at a more detailed level. ML system auditors can be internal or external to the firm that is employing a given ML system.

Finally, growing research and development efforts are being dedicated to technical solutions that automate the generation and recording of process information. Software-generated ‘audit trails’ and related concepts can contribute to the reliability and verifiability of some types of process information, while at the same time reducing the cost of recording and making the information available to stakeholders.